How to freebayes

Modern DNA sequencing would be impossible if not for high performance inference methods

As the price of doing so has decreased, sequencing genomes has become an essential part of biology. The revolutionary step in this space has been the development of short, “noisy” DNA sequence reads. Although designed conceptually in the 1990s, it was only in the early 2000s that technology allowed the implementation of these massively-multiplex sequencing approaches. The key was cheap, fast computers. These approaches would not work if algorithms to organize and clean the data were expensive to run.

The short (50-150bp) reads of DNA derived from the lowest-cost and most-popular contemporary sequencing technology must be organized (most frequently by alignment against a reference genome) so that we can then extract information about the genome(s) of the sample(s) we are examining in an experiment. The reads are relatively noisy, with error rates (1%) around an order of magnitude above the actual rate of variation we’d expect to find in a human sample (0.1%), so we cannot simply trust the information that comes out of them. We need to aggregate data across experiments and apply classifiers to the putative variations that we observe in order to reduce the error rate to something which can be used for downstream analysis. In the field the classifier that we run to do this is called a “variant caller”

So the typicaly contemporary sequencing workflow goes: sequence, align, call variants. The final result can be reduced to a matrix of genotypes over sites (and individuals, if many have been sequenced at the same time), and this is then generally usable for a wide variety of genomics tasks.

What does variant calling do?

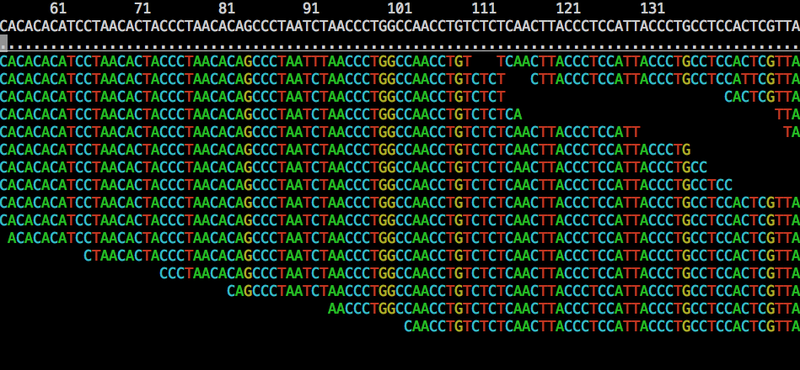

In variant calling we start with alignments (typically in BAM format) made by an aligner like bwa:

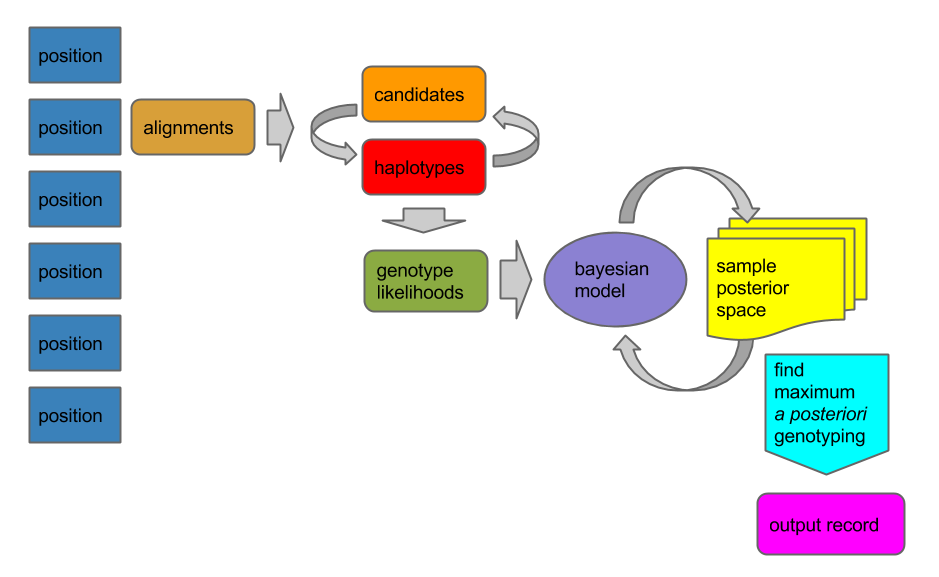

Then for each position in the reference we run a process that detects canditate variants and determines genotypes over a set of samples that we’ve defined in the input alignments:

The result is a file (a VCF file) that lists a series of variable sites an annotations that let us interpret the results, such as the call quality, the reference and alternate alleles, and genotypes for all the samples that are mentioned in the BAM file. You can do this in one step by giving freebayes a reference and BAM file, like so:

➜ test git:(master) ✗ freebayes -f tiny/q.fa tiny/NA12878.chr22.tiny.bam | grep -v "^##"

#CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INFO FORMAT 1

q 186 . T C 340.765 . AC=1;AO=16;RO=25 GT:DP 0/1:41

q 1008 . C T 484.25 . AC=1;AO=22;RO=17 GT:DP 0/1:39

q 1817 . GCCC ACCT 104.428 . AC=1;AO=9;RO=19 GT:DP 0/1:28

q 1917 . A G 466.669 . AC=1;AO=19;RO=18 GT:DP 0/1:37

q 2350 . T C 3.30386e-05 . AC=1;AO=4;RO=14 GT:DP 0/1:18

q 3263 . C A 7.50468e-06 . AC=1;AO=3;RO=12 GT:DP 0/1:15

q 4449 . G A 298.354 . AC=1;AO=13;RO=18 GT:DP 0/1:31

q 5009 . C T 761.008 . AC=1;AO=30;RO=14 GT:DP 0/1:46

q 5080 . A C 0.000474156 . AC=1;AO=9;RO=27 GT:DP 0/1:37

q 5095 . A G 8.19916e-11 . AC=1;AO=7;RO=27 GT:DP 0/1:34

q 5638 . CATA CA 270.936 . AC=1;AO=17;RO=13 GT:DP 0/1:30

q 6418 . G A 326.813 . AC=1;AO=14;RO=12 GT:DP 0/1:26

q 8846 . T C 329.36 . AC=1;AO=15;RO=30 GT:DP 0/1:45

For example, here we see that on the contig named “q” we have a high quality SNP at position 1008, a low-quality one at position 2350, and an indel at position 5638.

We can think of the variant caller as a kind of compressor for genomic data. In this example, which is a standard test run in freebayes, we take 300KB of alignment data and reference sequence and reduce it to a 16KB description of the variation:

➜ test git:(master) ✗ freebayes -f tiny/q.fa tiny/NA12878.chr22.tiny.bam | wc -c

16101

➜ test git:(master) ✗ ls -sh tiny/q.fa tiny/NA12878.chr22.tiny.bam

284K tiny/NA12878.chr22.tiny.bam 16K tiny/q.fa

freebayes is a Bayesian haplotype-based variant caller

For the past five years I’ve worked on a variant caller, freebayes. The project continues the work of Gabor Marth, who wrote the first variant caller of this type, Polybayes in 1999. He had updated it several times, eventually producing BamBayes, which was written in C++ and read the alignment format developed in the early phase of the 1000 Genomes Project. When I joined his lab in 2010 he encouraged me to start working on the next version of this software, which became freebayes.

Bayesian inference methods produce probabilistic classifications that combine new information (in the form of observations) with preexisting models (our priors) that could be derived from knowledge or our expectations of how a system works.

When applying Bayesian models to genomics, we model the genome or genomes we’re interested in to derive prior estimates of the distribution of genotypes and allele frequencies, and then incorporate read evidence by estimating how likely it is that a given set of reads derived from each one of our potential genotypes for each sample.

The basic idea follows directly from Bayes Theorem: P(Genotype|Data) = P(Data|Genotype)P(Genotype)/P(Data). We call P(Genotype|Data) our posterior— it’s our result, and we call P(Data|Genotype) our data likelihood— it explains how likely it would be to see a given set of observations given a particular underlying genotype. P(Genotype) is our prior. We use it to link in our expectations of how much variation there is in the genome(s) we’re considering and what kind of distribution of genotypes we’d expect to see.

It’s simple enough to set up a few models that let us think about a collection of individuals which are diploid or haploid, but in nature many organisms have higher genomic copy number, or are best thought of as having an unknown copy number. Also, it’s straightforward to work with only two alleles (such as biallelic SNPs), but in many cases we find more than one allele at a given genomic position, and this only gets worse as we think about larger regions of the genome and more individuals. So as to not exclude these kinds of contexts from our inference, we had to generalize the model that Gabor had developed to handle handle arbitrary ploidy and arbitrary numbers of alleles. This extension was the genesis of freebayes.

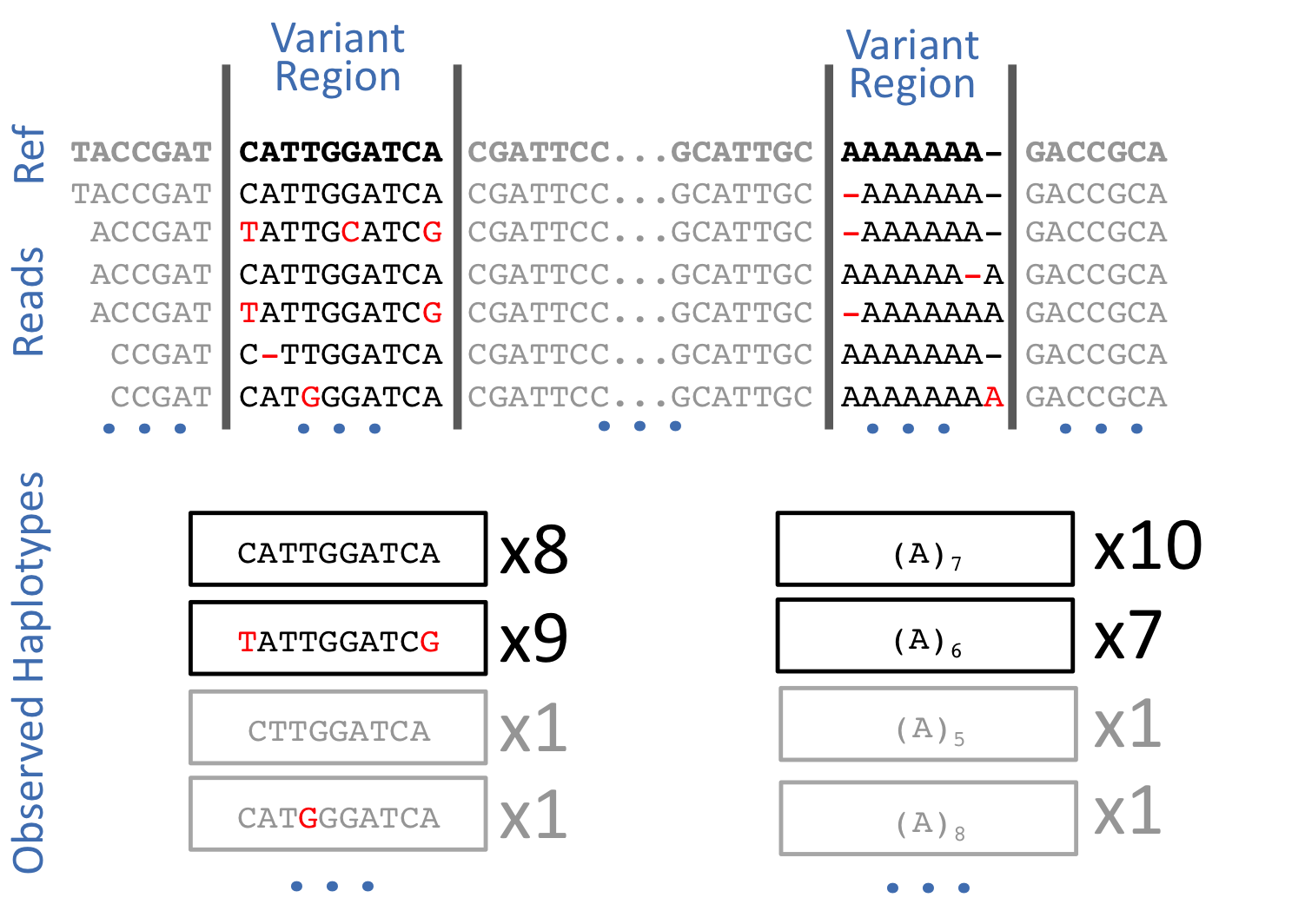

Then, I found that local alignment artifacts caused many problems when attempting to detect indels. I realized, as others had, that the read sequence itself is a more stable thing to work with than the output of the aligner. And so I generalized freebayes to operate directly haplotypes, or small bits of sequence, rather than just abstract SNPs and indels. The result was a kind of ultra-local assembler that would throw away the alignment information before trying to figure out what alleles it was looking at. Provided that errors are weakly correlated, considering haplotypes also has a strong effect on the signal to noise ratio of the process. The number of possible errors increases exponentially with the length of the haplotype, while the number of true underlying states remains constant. By considering longer haplotypes we tend disperse sequencing noise into many erroneous haplotypes that are unlikely to occur more than once, while the real underlying alleles continue to have strong support.

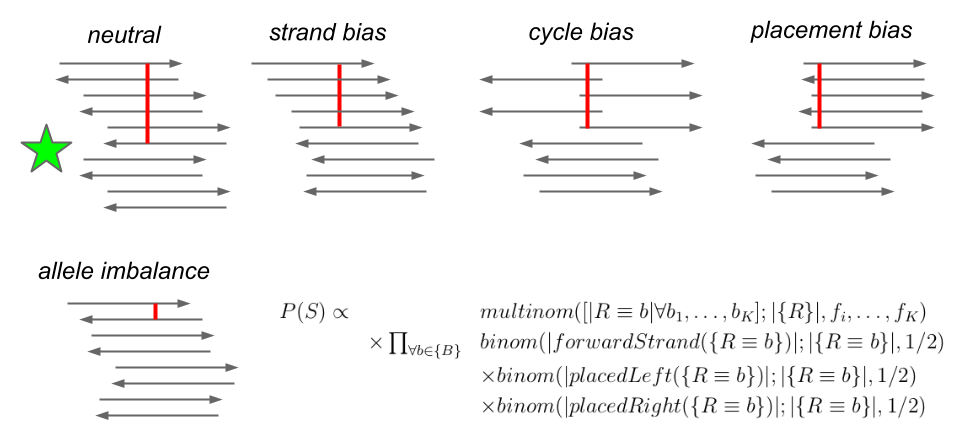

After working on freebayes for several years, I saw that many erroneous variant calls would have apparently strong support, but the reads at the genomic locus would look very strange. The supporting observations might only lie on one strand, or be aligned only to the left or right of the locus. The read quality might degrade as the sequencing process progressed, and a given allele might only be supported in the “tails” of the reads. These sources of error aren’t incorporated into the standard Bayesian variant calling model, and in order to account for them others have developed complex and costly post-processing steps which provide limited benefit to results but are now considered standard by many people working in bioinformatics.

Instead of implementing a post-processing step, I decided to extend the prior model used in freebayes to include an estimate of the sequencability of the locus and its alleles, which is termed P(S) in the following illustration:

This extension improves the performance of the method to be in line with what you’d get by modeling these factors post-hoc and recalibrating the quality scores. By including this directly in the model we greatly improve the usability of freebayes. In a single step, we can go from appropriately processed alignments to a highly accurate description of the genomes we’ve sequenced.

If you’re interested in the methods in freebayes, you can read the initial documentation on arXiv: Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. I’ve been working on an update describing all of the extensions I mention here, but right now it’s only available in the paper directory in freebayes’ git repo (cd paper && make will produce a PDF).

freebayes is a free software project

I have always been inspired by free software. It is a manifestation of the power of the commons to create value for society. Although 10 or 15 years ago this may have been a point of contention, it is now impossible to ignore the importance of the commons to the public good. Every day we use free and open source software. As of February 2015, 96.6% of web servers ran Linux, and so it is extremely unlikely that you have done anything on the internet today that was not enabled by a vast network of free software.

Free software is critically important to science, where reproducibility can be impossible without the genuine artifact of code that enabled a certain analysis. Virtually all bioinformatics is supported by open source software, and run in open source operating systems. Only a few holdouts in this space use proprietary licensing or distribute closed source products.

When I started working with Gabor on freebayes, he needed little convincing to allow me to release it under the extremely permissive MIT license, which effectively releases the code into the public domain under a waiver of warranty and attribution. If I were to do it again, I might have elected to use the GPLv3, as employed by other popular bioinformatics software, but this permissive license has ensured wide use of freebayes in a huge array of contexts (for instance, a performance-optimized fork of freebayes runs inside of the Ion Torrent device). The decision to put freebayes into the commons has provided huge returns on investment to our funders. However, the small space of variant detection is crowded and has been dominated by a proprietary platform, and we were unable to obtain new funding to specifically develop freebayes. Despite the lack of funding, interest in freebayes and its use has grown continuously as more biologists apply high-throughput sequencing techniques in their work. I have attempted to stay on top of maintenance even as I have begun to work on a new paradigm in resequencing informatics, but this has been difficult without support.

I’m working with DNAnexus to maintain freebayes as an open source project!

I am very happy to announce that I have been collaborating with the research team at DNAnexus to develop new extensions to freebayes! Their support has already helped me implement basic gVCF support in freebayes, and we have a bunch of improvements queued up that should ensure that freebayes continues to be useful to the community well into the future. This post coincides with DNAnexus’ announcement about this work on their blog.

In addition to supporting me in the development of new features, they’ve asked me to continue providing technical support via public channels, such as on the freebayes issues page and mailing list, and also on this blog, where I plan to dive deeper into documentation of the many facets of the method.

Our arrangement obligates us to keep everything in the open, and I think it can serve as a model for how industry can support the public commons for the benefit of all. I’d like to say “thank you” to the team at DNAnexus, and also to all of the researchers who are using freebayes to further our understanding of the natural world! I’m looking forward to enabling some really cool research.

(By the way, I should make clear that the views on this blog are mine, and are not meant to represent those of DNAnexus.)